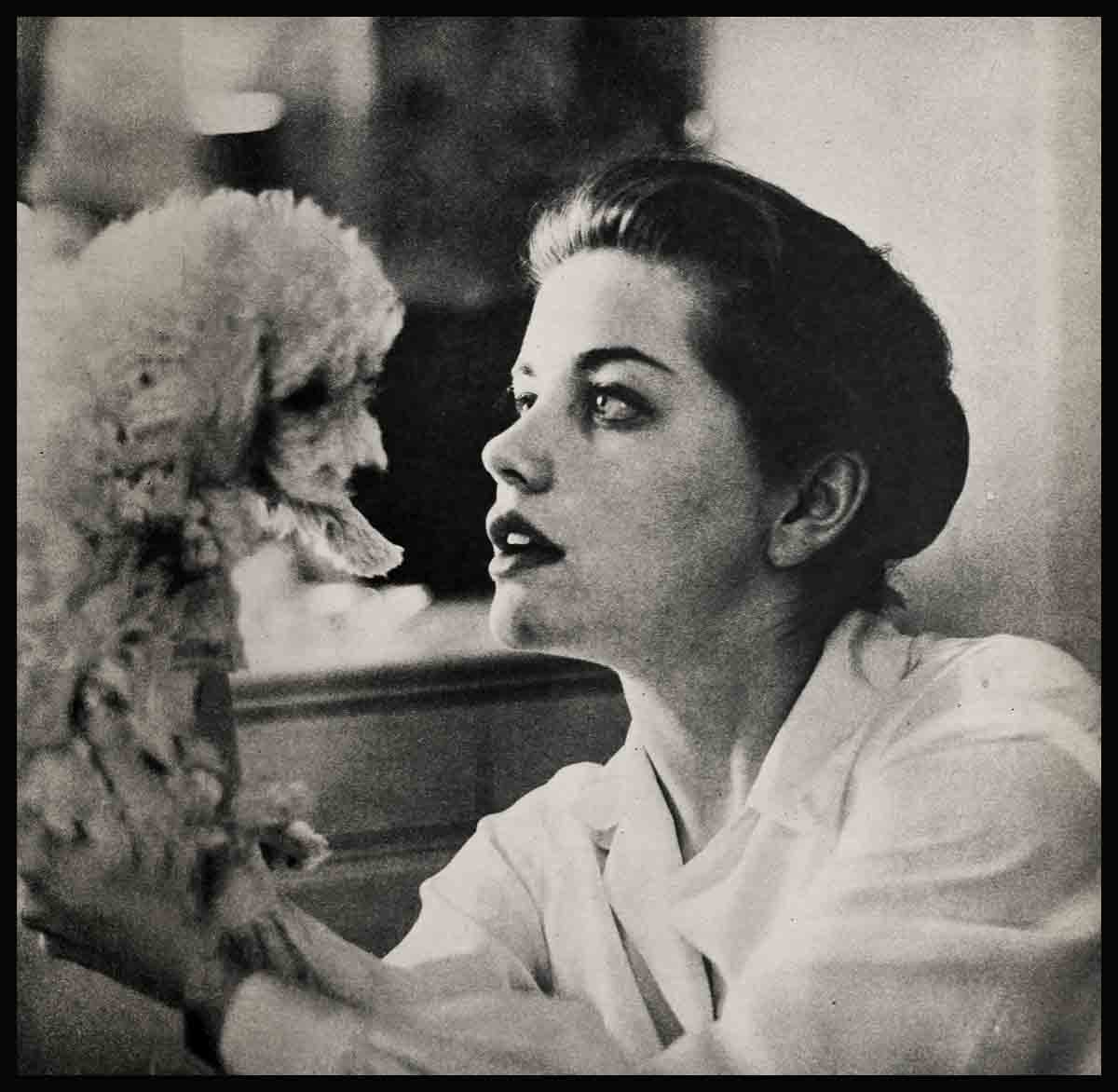

How Dolores Hart Learned About Boys

It happened the night my daughter, Dolores Hart, made her Broadway debut in “The Pleasure Of His Company.” Suddenly a boy was putting his arms around her and kissing her. Only it wasn’t on the stage. It wasn’t make-believe. It was for real. I’d come prepared to weep, prepared for a shattering emotional experience—but for other reasons, safe reasons up there on the stage. But not this. It caught me completely unawares!

You see, it was the first time I’d ever seen Dolores kiss a boy! Except for Elvis Presley on the screen. But this was different. Dolores wasn’t playing a part in a picture. The boy who kissed her was expressing his own feelings, his own affection. In accepting the kiss, Dolores was doing the same.

Not that I disapproved Er the act, or of the boy. I knew Dick in Hollywood. He’d flown East just to wish Dolores luck on her opening. He was a fine boy, and he’d been interested in Dolores for some time. Still I had the oddest sensation when I saw Dolores kiss him. It kind of shocked me, I guess—not in outrage, but into belated awareness. I’d always thought of her as a little girl, and all of a sudden I realized she had grown up. All of a sudden she was a big girl. Holy Toledo, was she a big girl! She was about the biggest girl I’d ever seen.

Yet the curious thing is that Dolores always has been a big girl—even when she was a little girl, if you know what I mean. It occurred to me as she and Dick kissed how remarkable it was that in all her 20 years I’d never had any problems with Dolores about boys. Considering her beauty, I think most people will admit that’s quite unusual these days.

Especially since she turned out so well, I’d like to think I taught my daughter much of what she knows about boys. But I find it hard to sun myself under that illusion. She was born with built-in good sense. I doubt that I ever told her anything she didn’t already know or sense—or that I ever warned her of any danger against which she was not already on guard.

Not so long ago—in fact, shortly before she left to do her Broadway play—Dolores came to me and told me about the difficulties she was having with a boy she knew. He was of the same faith as Dolores, and he had tried to persuade her that their having a religion in common would justify the liberties he obviously wished to take. But Dolores was appalled by his reasoning.

“You know Mother,” she was anxious to tell me about it, “it seems to me that he was using his religion to provoke an affinity. And Mother, I do not feel any attraction for him just because of that. I know in my heart that when the time comes the right feeling certainly will be there, but I could never feel obligated to demonstrate affection because of false religious professions.”

I didn’t have to help her think out her problem. She already had thought it out on her own. All I could do was nod, and offer silent prayers for her innate wisdom. Nevertheless, Dolores made me feel that my approval was very important to her. She seemed so relieved that I agreed with her that she made me feel as if I had helped her work out her problem. Yet if she hadn’t chosen to confide in me, I would have had no idea it existed.

From earliest childhood, that has been a characteristic of Dolores. Most mothers shudder as they recall the delicate years of steering their daughters through adolescence. Dolores, bless her, spared me that agony. She always had better sense than anyone in a long line of Bowen girls—all of whom, like myself, married at 15, 16 or 17. I remember that when I was a little girl I thought someone should have talked to me, but they never did. I just thought it would be a good idea. With Dolores, it has worked the other way around. It seems to me that Dolores always has given me her shoulder, always has been comforting me, saying, “Don’t cry, Mother, I’ll take care of you always.”

With such a lovely daughter on my hands, I won’t pretend I didn’t feel the same anxieties as other mothers. Dolores and I have talked many a night under the moon and all that. We’d go out in the backyard, sit in the chaise lounge and talk girl talk. Once when Dolores was 11, I mentioned the dangers when a girl is promiscuous.

“Mother,” Dolores asked, “what is promiscuous?”

“That’s when you know in your heart what you’re doing is wrong,” I replied.

I don’t think Dolores has ever forgotten that. I know she’s never done anything that she felt in her heart was wrong. I guess she’s had God’s hand on her shoulder. She has so much heart. That’s what makes me happy. It’s Dolores’ heart.

We looked forward to our occasional chats, and we had another one of them when Dolores started dating. It was never a case of Mom reading the riot act. We always had a wonderful affinity. It was a thing we felt together. We always had a communication.

Birds and bees time is very delicate, and too many parents shy from facing it, sometimes at high cost to their children. My own parents, for one reason or another, never got around to discussing it with me. Although I can gratefully say that God has been kind to me, I certainly could have been none the worse if my folks had seen fit to acquaint me properly with the facts of life.

“Sex is not wrong,” I assured Dolores. “It’s God’s creation. It’s the way God makes living things. There would be no such thing as children if not for sex. Therefore it’s right and beautiful—when its sanctified by marriage.”

I said it as an act of duty rather than necessity. I didn’t really have to tell this to Dolores. She knew it already. I have often suspected: that she was born with the heart of a saint. If no one ever had spoken a word to Dolores, I fully believe she’d never do anything wrong. She just happens to be about the sweetest thing that God ever put into the world. And if I sound prejudiced, who has a better right to be?

“Just be good,” I would tell her. “Just be clean. Never lie to yourself and never lie to your God.”

When she was 12, I said to her, “Sweetie, look, you’re a big girl now. One day you will get married. Until then there are certain rules you have to keep. You’re just a young girl, but by all means keep the rules.”

Above all—if I can take credit for one thing—it’s not so much what I said to Dolores as she grew up. but how I treated her and her hoy friends. I never doubted her or them, never spied on them, never questioned them. I gave her freedom, and in return she gave me full vindication.

Dolores has just turned 20. She’s a teenager no more—a child no more. Yet I can honestly say I never treated her like a child. In all her teens, I can recall imposing only one restriction on her.

The first time a boy asked for a date, he wanted to take her in his car. He was a real nice boy from a very nice family. But I just didn’t think it was safe for teenagers to drive at that particular time. It was simply a question of not risking an accident.

“Go ahead and keep your date,” I told her, “but do it on foot.”

So they walked to the La Reina Theatre, and they had a grand time.

That was the only don’t I invoked. Any other don’ts that Dolores may have enforced were, I’m sure, a result of her own good judgment—and religious training.

Later, when Dolores herself learned to drive, I had no objection if she drove with dates. I felt if she could drive, why couldn’t she get herself out of any situation? I told her only one thing, “Too easy, too late.” It was a word to the wise, and Dolores, being quite wise, it was entirely sufficient.

I practiced an open door policy. It always was open house and a big pot of spaghetti. I’d open up the doors and always bring the kids in. I’d have 3 or 4 girls over for a sleeping party. I never made Dolores feel guilty about asking a boy over, and there’s never been a boy to the house who ever was poorly behaved or disrespectful. They’d always be on their own. They would take her to Mass, go to the movies, sit and listen to music, work on various projects in the garage. They always had a good and wholesome time without my hovering over them. So often Dolores would have a boy over, and my husband and I would seclude ourselves in another part of the house instead of our presence annoying. It seems to me so simple. It makes for better children—if Dolores is any criterion, and I most certainly think she is.

Dolores never did anything clandestine. She didn’t have to. She always knew even. before she asked that I gave her credit for knowing how to conduct herself, and that my consent would be given as a well-earned vote of confidence.

“May I have a sleeping group over this weekend?” she would ask.

Always the answer would be yes.

The time to worry—and, tragically, by then it’s usually too late—is when a girl feels she has to sneak around behind your back.

I’ll have you know that Dolores was playing with boys long before she ever thought of dating them. She always was running around in sweatshirt and jeans, tinkering with things, keeping busy, using her hands. I’m sure the boys rarely ever thought of her as a girl. She was just their equal. She’d get on the roof and help fix the TV aerial. She’d help mechanically and repair things. Shed always be in the garage working on projects with boys from the neighborhood. She’d work with them on puppet shows. They’d get together and paint—I mean art, not the side of a barn. They used to take bikes apart and put them together again, fix electric plugs. Long before the picture called “The Fly” was made, they had a science project and built a big mechanical fly. The garage was a community gathering place. She had the most wonderful rapport with the boys. They weren’t sweethearts. They were comrades.

Often she’d bring lizards and snakes into the house, and oh, how she’d infuriate me. She’d bring in a lizard and stroke his back, and I’d almost faint.

“But Mom,” she would say, “Gabriel got him for me.”

As if that somehow made it different—and somehow it did!

From earliest childhood Dolores was at ease with boys, and they were at ease with her. They were comfortable with her. They liked her, and they respected her. They liked her so much, in fact, that not until recently did they stop to reflect on how lovely she is. The result was, I offer deep thanks, that she came out knowing how to handle herself and how to handle them.

In those carefree days, Dolores learned one of the most important factors in getting along with boys. She works with them—not at them: And she knows that what was true in the garage when she was a member of a neighborhood do-it-yourself pack, has to be true in her later relationships with men.

“When the time comes that you decide to get married,” I told her, “and you want to be loved, you have to give love. You don’t have to work at it. It comes to you, and when you give, it comes easily.”

Fortunately, Dolores has the rare capacity to learn from the mistakes of others. She learned one of her biggest lessons from a mistake of mine. I married too young. Neither of us was old enough when we married, and we naturally paid for this mistake in frustration and unhappiness. We really were much too young to know what we were and what we wanted out of life—and it was inevitable that our marriage should fail. Dolores has been very sensitive to this experience of mine.

And she has had more than her share of opportunities—if not temptations—to marry young. When she attended Corvallis High School, one of the loveliest and most popular young ladies on the campus, more than one hopeful young man set his cap for her. Once when what she thought was merely a good friendship ripened into emotional involvement on the part of the boy, he asked Dolores to become his wife. Of course, she had to refuse him. But she did it as gently and honestly as she could. She explained her own deep-seated distrust of early marriages, and cited my experience as one of the reasons for her thinking.

“My father is a wonderful man and. I love him dearly,” she told him. “I feel the same way about my mother. And I can see myself how their worlds really could not work out together. You can’t say it’s either person’s fault in a situation like that. The only fault is that they didn’t give themselves an opportunity to grow up before they married.”

She was terribly upset when she came home. She felt dreadful about hurting the boy’s feelings.

“Oh Mother,” she was close to tears, “I do so hope he understands and doesn’t feel too badly. I pointed out we both were going to college in the fall, and what’s more, to different colleges. I explained I wasn’t in love with him to the point where I’d give up the thought of going to college to marry him. Even if I thought I was in love, I wouldn’t trust myself. There were too many possibilities I might be reacting to emotional things.”

I put a comforting arm around her.

“If it really was love,” she continued, “waiting and seeing what happened to our feelings wouldn’t hinder it, would it? For any teenager, a love strong enough to end in marriage should be able to stand the test of waiting, of seeing other young men. Don’t you think so, Mother? No ring around your finger or ring around your neck would be a protection. A wedding ring is not a magic wand that would ward off other intrusions. If seeing other young men would interfere with love, the love isn’t solid. I told ‘him it was so silly to put this test to it. I feel that love is not an obligation. It’s the way you feel, not the way you should feel.”

Such maturity was not unusual for Dolores. She displayed it throughout her teens. Her own determination to give herself an opportunity to grow up before considering marriage was unwavering. No amount of pressure from marriage-minded boy friends could budge her.

I was so grateful that she understood the avoidable heartbreak I had endured. Naturally I didn’t want her to marry as young as I did. I wanted her to express herself first, to do all the things a girl should do and to meet all the people a girl should meet before giving herself to marriage. I didn’t want to see her waste her youth. I think marriage is wonderful, and I’d like to have ten grandchildren. But I’d like to see Dolores have a lasting marriage, good for 50 or 60 years. I wouldn’t want her to go through two or three marriages. It’s a good thing when a girl can say to herself, “I give myself to one man.”

But Dolores scarcely needs any urging from me to think along these lines. It always has been her dearest and unswerving dream to love one man and-one man alone, forsaking all others. So many times, even when I have been impressed with a boy friend, she would chide me, “I know he’s a very nice boy, Mom, but I’m just not ready yet. There’s so much I want to do first.”

She always has been very frank with boys about her aversion to going steady. She’s discussed this with me many times, and I’ve always been amazed at the clarity and maturity of her thinking. Verily, it was as if I were the daughter and she the mother.

“The basic reason most teenagers go steady, Mom,” she would tell me earnestly, “is not because they’re in love with one person. Its because the need for a feeling of security is stronger than their need for a feeling of independence. Most girls I know who go steady do it mainly so they’ll have a date next Saturday night, so they won’t have to run the risk of somebody not asking them out. Then tend to romanticize too much. A lot of times ifs just because it’s the time of the year, or the thing to do. It’s because it’s the fashion in the crowd to be madly in love with somebody.”

Dolores always had one test that she not only used for herself, but which she persuaded many of her classmates at Corvallis to apply when they were tempted to go steady.

“A girl should ask herself one simple question,” she said. “Would she give up anything she valued very much in order to go steady? For instance, if she had a chance to go on a vacation, to get a new wardrobe, if she had a chance to do any of a variety of silly mundane things, if she had the chance to do all these things, would she willingly throw over this mad, wonderful romance that she was so very involved with?”

Many of the girls at Corvallis actually followed Dolores’ counsel, and they always seemed happier when they decided they had plenty of time to go steady, after all.

“Kids deprive themselves of so much fun out of early life by getting tied down with one person,” Dolores would tell me soberly. “They don’t give themselves a chance to grow. They see only one facet of life. There are so many undeveloped potentials when you’re in your teens, which are still formative years. You squelch so much of yourself to the point where you become smothered. You give up all chances of doing something later in life, and by the time you’re 19 or 20, you’re tied down with a baby. Kids who go steady say they have no intention of getting married. Then why in the world go steady if you have no intention of getting married?”

Dolores spelled it out much better than I could.

“The dating years,” was her point of view, “are the only time to go shopping, to find out what kind of person suits you best. You’re not giving yourself a chance if you don’t examine the various personality types.”

She would see hazards in steady dating that I frankly did not even visualize.

“If the second or third time you’re let out of the house you decide to go steady,” she pointed out, “and you end up dating: the same boy for three or four years, you’re in for a jolt. Suddenly dawn hits him. He realizes he’s only a kid, and he’s got a lot of living to do, and he breaks it off. If a girl thinks it’s hard to get a date while playing the field, she should try getting a date after she’s been out of circulation four years.”

In her forthright manner, Dolores didn’t avoid the moral implications of steady dating, either.

“Gee, Mom, boys and girls in their teens awaken to emotions they’re not used to,” she recognized the core of the danger. “Too often unfortunate experimentation leads to difficult situations kids wouldn’t get into if they weren’t in constant association with one boy week after week. There are certain intimacies, petting and so forth, going on which really shouldn’t take place between boys and girls these ages. A girl should have a certain reverence about herself. She should have a knowledge that there’s a time and a place. Often just because a girl is going steady she feels obligated to permit liberties. When she does, she feels a shame that is bad psychologically for her. It is hard for her to realize until too late when she has gone too far.”

The incredible thing—I just gasp when I think about it—is that these are things Dolores would say to me. No wonder I found it necessary to say so little to her.

Yes, I’ve always known Dolores was grown up, so very grown up for her years. But the first time I actually saw her kiss a boy brought home to me that she is not only grown up in thought, but in fact—that my daughter has blossomed into womanhood, a woman with the will, the character and the gift of talent to meet every experience in life—not the least of them marriage.

It’s difficult, in Dolores’ case, to pinpoint exactly how she learned about boys. But how well she learned, and how wholesomely!

No mother could wish for more. Certainly not this one.

THE END

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1959

No Comments